Protected characteristics and careers in anaesthesia

Intersectionality in relation to EDI and DA differences in different workforce groups

Authors:

- Dr Sophie Jackman, ST4; Anaesthetist in Training Representative on RCoA Council

- Dr Sarah Thornton, Education, Training and Examinations Board, Chair

When you examine the data from the GMC about our specialty, it gives an interesting picture. It demonstrates that your gender, pattern of working and ethnic background have an impact on progression and job title. In this article, we explore this more closely.

As many of you will know, differential attainment is an area that the College has a major interest in tackling and that we have been working hard to improve. Tackling differential attainment properly covers all aspects of career progression, not just exams.

Through examining the GMC’s survey of anaesthetists in training, recruitment data, and progression data, we can see a picture that shows that if you are black, Asian, female, or have an international medical qualification, you will be overrepresented in the cohort of SAS doctors, and that the more of these characteristics you have, the greater that overrepresentation will be. The female percentage of SAS doctors has risen from 33% in 2010 to 42% in 2020, and 81% of those on SAS contracts are non-UK graduates.

Female consultants made up 38% of the workforce in 2020, compared with 28% in 2007. The proportion is even higher when looking at anaesthetists in training and non-consultant roles. Overall, these grades of doctors are 47% female compared with 38% of female consultants.

We know that people choose an SAS career citing the work/life balance or early geographical stability – excellent reasons to do so. However, some choose an SAS career because other options are less accessible to them. Everyone’s career should be determined by their personal ambitions and life choices, and we should be concerned that disproportionate representation of protected characteristics could indicate biased processes that should be addressed.

The factors that determine this overrepresentation are many. We know that in 2022, 310 anaesthetists joined us from abroad – 38 as consultants and 272 as SAS doctors – demonstrating the importance of SAS as a route into NHS practice for overseas doctors. In fact, overseas doctors are increasingly choosing the SAS route rather than the consultant route – a fact which deserves exploration in its own right. However, this is not the total picture: we also know that in the 10 years to 2024, the number of anaesthetists with an international primary medical qualification has actually declined to 31%, when the UK average for all specialties is 41%.

If our specialty is becoming less diverse, despite our continued reliance on recruiting from abroad, we need to look at our routes of entry. We are one of the least diverse specialties in terms of recruitment into training and, as Dr Watson and Dr Wong tell us in the Antiracism in anaesthesia podcast, 302 black doctors applied to anaesthetics training in 2023. Of those that we interviewed, they scored five points lower on average at interview than white doctors, and we only made offers to five of them. Additionally, we know that at ST4, Asian, black, or mixed-race doctors score 2.5 points lower on average than white doctors. Hence, perhaps more of them are choosing to take specialty roles to progress towards the portfolio pathway, or are just carrying on with their lives in a more settled and satisfying career without the disruption and difficulty that a national training number can bring.

So, what factors are at play here to cause this differential attainment?

The barriers to appointment are the MSRA at core, which has been shown to have an attainment gap. This gap is currently being addressed nationally by MHRA and by the RCOA with more anaesthetists on the board and newer questions. Self-scored portfolios bring another hurdle that challenges minority groups. While the actual reason for the disparity in score is unclear, we know that women and minority ethnic groups underscore themselves in self-assessment, or perhaps these candidates may not have had access to the same opportunities to enhance their portfolios. However, for overseas doctors not used to the UK system, it may be that they are not presenting the information in the best way to showcase themselves. Delivering a successful interview is similar to the exam; technique is paramount to sell yourself in a short time frame, and that inevitably gives an advantage to UK white candidates born into a system designed for them.

An alternative route to training is the portfolio pathway. Analysing last year’s portfolio applications shows that men are 1.5 times more likely to apply than women – although reassuringly, both genders showed equal rates of application success and IMGs slightly outperformed UK graduates; 59.8% of male IMGs compared to 52.5% of female IMGs were successful.

There is still work to be done in addressing differential attainment in the FRCA. Since 2015, we have improved the FRCA pass-rate gap from 11% to 5% between white and minority ethnic groups; however, clearly, there is still work to do.

One of the routes we are using to achieve this is by recruiting more examiners and associate examiners from diverse backgrounds, as well as running differential attainment master classes and providing unconscious-bias training for examiners. In the last year, we have successfully recruited 25 new examiners – 20% IMG. They are 40% female – up from 27% the year before, although there is only one SAS doctor. Female examiners now form the majority – 57%, at Primary, although male predominance remains at Final and also in FPM and FFICM. We are very keen to recruit more SAS FRCA examiners – if you think this could be you, please get in touch!

All doctors deserve equal access in training and throughout their careers to the opportunities and rewards that practising anaesthesia brings. While it is fully expected that the SAS workforce and portfolio pathway will continue to grow in popularity, it is our responsibility as a college to make sure this is done in a fair and equitable manner.

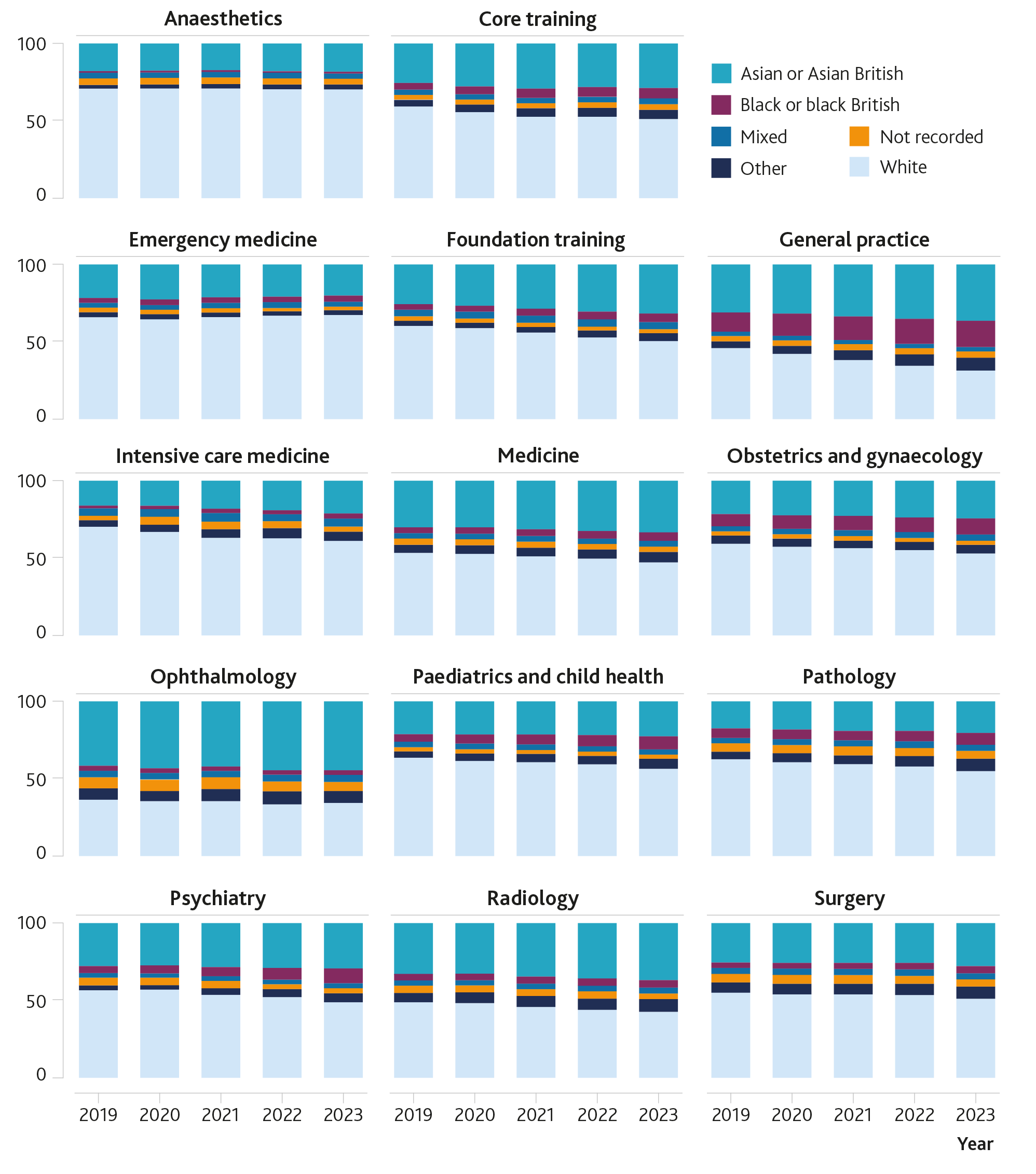

Figure 1: Ethnicity proportion by postgraduate training programme, by year

Source: The state of medical education and practice in the UK: Workforce report 2024. (© GMC)

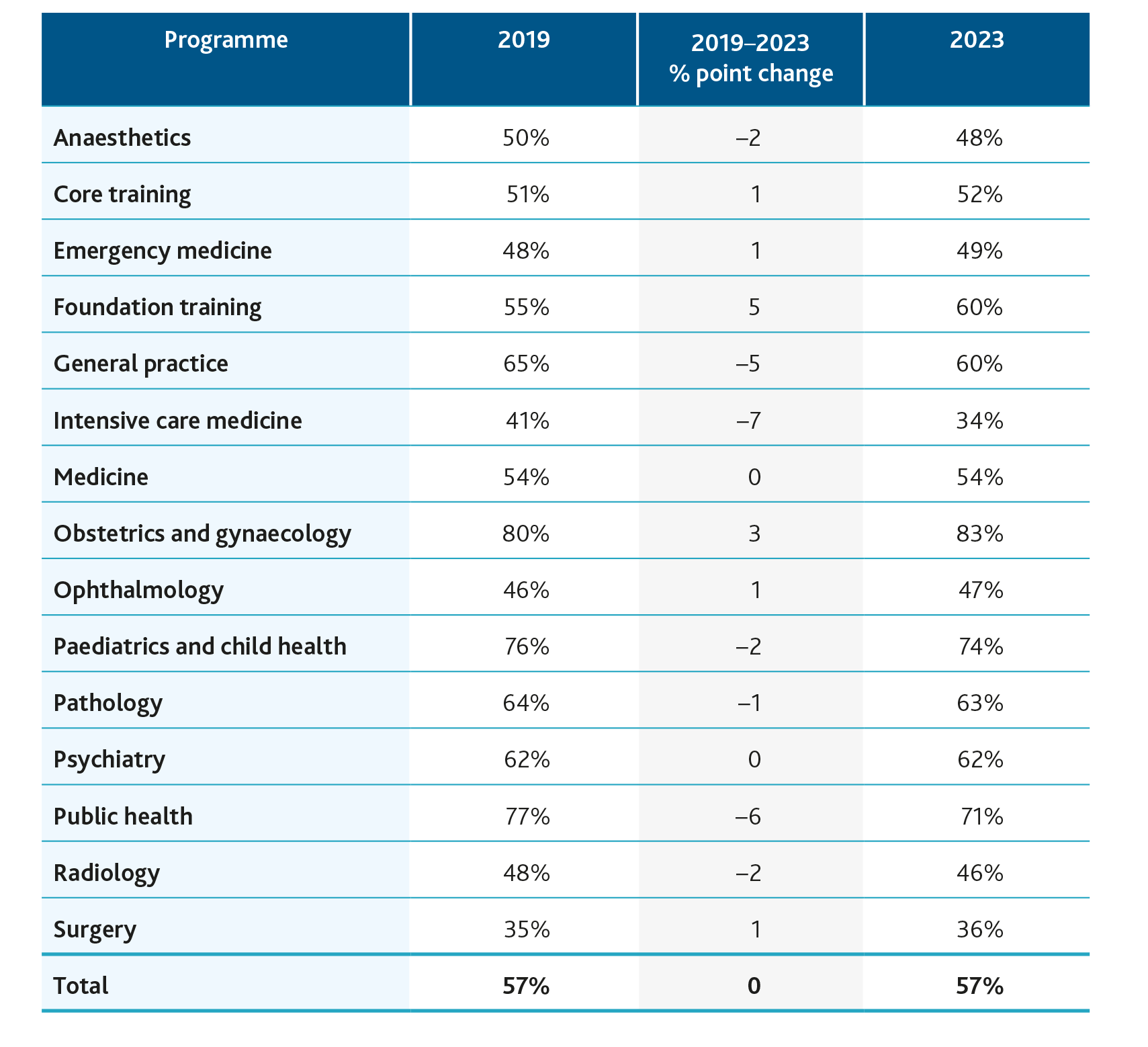

Figure 2: Proportion of female doctors across training programmes

Source: The state of medical education and practice in the UK: Workforce report 2024. (© GMC)

Many thanks to Derek McLaughlan for the Sunday afternoon he gave up to look at all the portfolio pathway demographic data for us.