- Bulletin: Summer 2025

- Opinion

Perioperative care for patients with learning disability and autism

Helpful advice and resources on treating patients with learning disabilities as they undergo surgery or other procedures.

Authors:

- Dr Corinne Rimmer, Consultant Anaesthetist, Royal Lancaster Infirmary

- Professor Andrew Smith, Consultant Anaesthetist, Royal Lancaster Infirmary

Andrew Smith is an elected consultant member of Council of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. These views are his own.

People with learning disabilities are sometimes thought of as being ‘challenging’, ‘non-compliant’, ‘awkward’ or ‘difficult’. Such language betrays a perspective where they are expected to behave in a certain way, that is, like ‘everybody else’.

They may indeed seem professionally and sometimes personally challenging to us, but the patient with learning disability is just as challenged, if not more so, by the people, systems and environments of healthcare that they encounter. Here we review the principles of care for this group of patients as they undergo surgery or other procedures and highlight some newer helpful resources.

The social model of disability holds that disability is not caused by an individual's health condition, or impairment itself, but by the way society treats and creates barriers for people with different needs. These barriers can be either attitudinal (such as unconscious bias, discrimination and stereotyping), organisational (such as inflexible policies or procedures), or environmental (such as barriers caused by accessibility or sensory difficulties). In addition, although autism and learning disability are distinct conditions, they give rise to many of the same needs and adjustments, especially if sensory difficulties are present. Three recent publications are available to help.

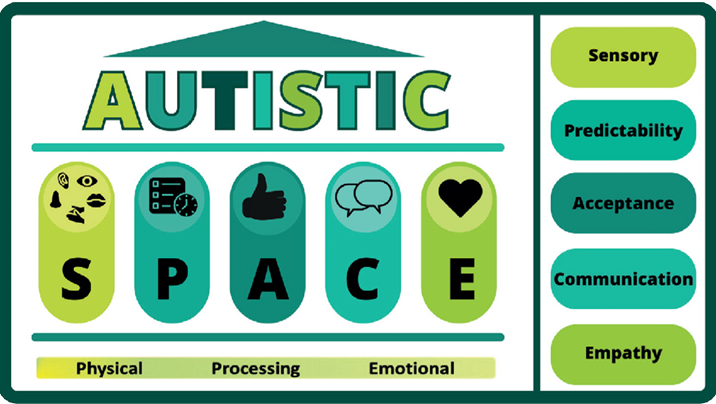

- The SPACE model has been proposed as a reminder that people with autism and learning disability need more space – whether emotional, physical, or processing space – than most patients (Figure 1).

- The National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi) has produced a Green Light Toolkit to enable organisations to audit how well they meet the needs of people with learning difficulties and autism.

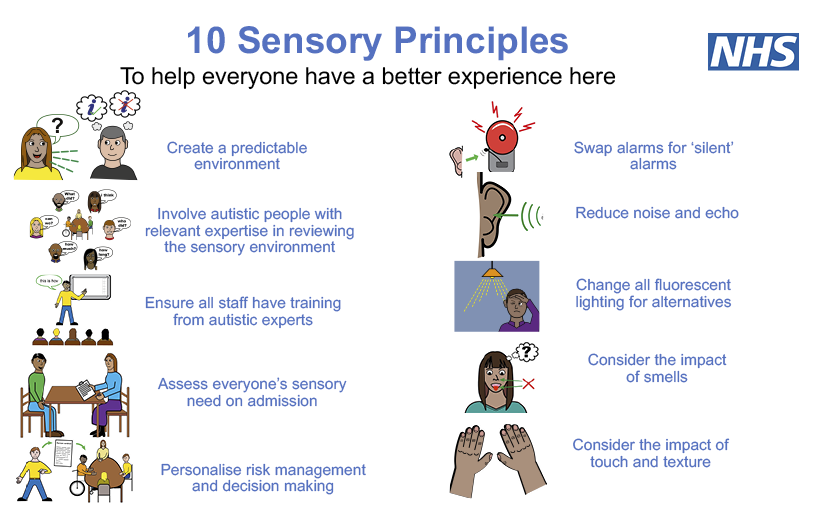

- Lastly, NHS England now has a ‘sensory-friendly resource pack’ including the infographic in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Autistic SPACE framework

Reproduced, with permission, from the British Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Figure 2: 10 Sensory Principles (NHS England)

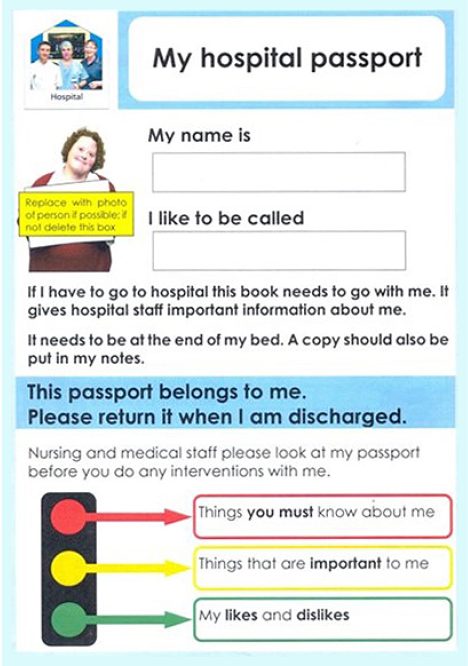

Preparation and planning are vital, and involving the learning disabilities specialist nurse will be invaluable in coordinating community services. Ideally, the patient will have a hospital passport. These were initially on paper, but in most trusts are now incorporated into the electronic patient record. This can be an extremely useful resource, as it details the patient’s communication needs, preferences and aversions, as well as important medical information (Figure 3). Looking at this document before meeting the patient is ideal, as the information can be used to develop a rapport with them. Parents and carers are also very helpful. From the information available, decide how flexible you need to be and what reasonable adjustments must be made to the hospital routines.

Figure 3: Example page from a hospital passport template

For elective cases, ‘practice visits’ to the hospital and operating theatre can be arranged before the operation date. An anxiolytic can be prescribed to be taken at home. Starvation rules may need to be relaxed slightly to allow medication to be taken in the usual way. Plans can be put in place for where and when the patient will be admitted, eg, a side room, a quiet treatment room near theatres, or even members of the theatre team meeting them in the car park. Avoid long waiting times (instead, staff must be willing to wait for the patient!) and having to pass food/drink outlets on the way into hospital or to theatre.

Make a ‘plan A’ and a ‘plan B’, but be prepared for neither to work. You may have to be flexible and adapt to the situation in front of you, and here, other members of the theatre team who are experienced with this group of patients may be able to help improvise a course of action. Parents, carers, and toys or other comforting items are all welcome in the anaesthetic room. Using a quiet, calm voice avoids the distress of having too many people talking at once. If the patient has a good rapport with one particular member of staff, for example, an ODP, nurse or support worker, we suggest that they can be encouraged to be the ‘main communicator’ with the patient.

Sedation is often also needed, even when all the above are attended to. Midazolam is our usual choice, in a dose of 0.5 mg/kg up to a maximum of 20 mg, either orally or in a buccal gel. Some patients cannot, or will not, agree to this, but we also have concentrated intranasal midazolam premixed with lidocaine, which, if the patient can be persuaded, works within 5–10 minutes of being atomised into one nostril.

Sometimes, even with the best planning, the patient can begin to get distressed. There should be an openness to changing tack if anyone in the hospital team, or a carer or relative, expresses unease at how things are going. Physical restraint (now more usually referred to as ‘reactive’ or ‘restrictive interventions’), should not be a part of routine care, and the best option may be to abandon the procedure and try another time. NICE Guideline 11 (2015) includes sensible advice on the use of such interventions.

We hope that these principles of care are helpful. It is vital that we treat all patients, including those with disabilities, with dignity, respect, and without discrimination, and do our absolute best to break down barriers.

See our ‘tips and tricks’ sheet for more information.