Risks and side effects – becoming confused after a general anaesthetic (delirium)

About this leaflet

This leaflet is about the risk of becoming confused after a general anaesthetic and surgery. This is known as ‘delirium’. It explains the causes of delirium and what can be done about it.

General anaesthetics are medicines that give a deep sleep-like state. They are essential for some operations and procedures. During a general anaesthetic, you are unconscious and feel nothing.

You can read about different types of anaesthetics in our Patient information leaflets and video resources section.

What is delirium?

Delirium is a sudden change in brain function that causes a person to become confused and disoriented. For example, it can happen at the time of an infection or after surgery and general anaesthesia.

Symptoms can vary greatly from person to person. For some people, symptoms can be severe and last for months. For others the effects do not last long. Delirium is caused by many different things and can be difficult to prevent. There are things that healthcare professionals can do to treat it if it happens.

How likely is it to happen?

The risk of delirium varies for each person, depending on different things. The risk is higher if:

- you are over the age of 60; the older you are, the higher the risk of developing delirium

- your physical health is poor at the time of surgery

- your cognitive ability (thinking, remembering, reasoning, etc) is impaired at the time of surgery

- you have dementia or a condition that affects your brain

- you have a mental health condition

- you take lots of medications for different medical conditions

- you drink a lot of alcohol

- you take recreational drugs

- you have difficulties walking and moving about

- you have poor eyesight or hearing

- you need emergency surgery.

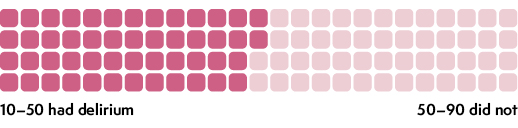

Out of every 100 people

Some types of surgery can also increase the risk of developing delirium. The following table shows how many people developed delirium after certain operations:

| Surgery | Out of 100 people |

| Urological (bladder) | Approx 5 developed delirium |

| Orthopaedic (on joints such as knee) | Approx 12 developed delirium |

| Head and neck | Approx 17 developed delirium |

| Abdominal (tummy) | Approx 28 developed delirium |

| Peripheral vascular (smaller vessels/blood supply) | Approx 39 developed delirium |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm (large artery/blood vessel) | Approx 43 developed delirium |

| Heart bypass | Approx 44 developed delirium |

| Hip fracture | Approx 50 developed delirium |

These numbers come from research studies involving people aged 60 years and older. You can find out about the research we used in our Anaesthesia and risk evidence table.

If you are having planned surgery (non-emergency), you should be invited to have a preoperative assessment, during which the healthcare team will look at your health and assess your risk of developing delirium. They may refer you to a geriatrician (a doctor who specialises in age-related medical conditions) or a specialist anaesthetist to optimise your medical care and reduce the risk of delirium.

Is delirium the same as dementia?

Delirium is not the same as dementia, although the symptoms can be similar. Dementia is a progressive disease of the brain. However, people with dementia are more likely to get delirium.

In some cases, the symptoms of undiagnosed dementia start to show after surgery. A small number of people in this situation can continue to experience a worsening of their cognitive ability for longer than usual or may not go back to how they were before surgery. In these situations, they may require support from a GP or a memory clinic.

What does delirium feel like?

Delirium feels different for everyone. Some people feel agitated. Other people become quiet and very sleepy. Symptoms tend to get worse in the evening and during the night.

Symptoms can include:

- not knowing your own name or where you are

- not knowing what has happened to you or why you are in hospital

- being unable to recognise family members

- sleeping during the day and being awake at night

- emotional changes such as tearfulness, anxiety, anger or aggression

- being incoherent, shouting and swearing

- trying to climb out of bed

- becoming paranoid and thinking that people are trying to harm you

- seeing and hearing things that do not exist (hallucinations).

Delirium can be frightening, not only for the person who is affected, but also for their relatives and friends. If it happens to you, your hospital team will make sure that you are safe and have the support that you need.

How is delirium treated?

If you develop delirium soon after surgery, your hospital team will work out what the causes might be and deal with those quickly. This might include:

- giving you antibiotics to treat any infection

- treating any pain

- adjusting medicines that might be contributing to delirium

- giving you additional fluids

- helping you treat constipation (difficulty with bowel movements).

If delirium is very severe and there is a risk of harm to you and others, you might be given a sedative – a medicine to make you feel calm.

Your hospital team will also do other things to help you come out of delirium and make you feel less confused.

For example, they might:

- provide a regular routine, a visible clock and natural daylight

- offer brain-stimulating activities, for example, puzzles and reading

- encourage you to wear your glasses and hearing aids

- allow as much visiting from family and friends as possible

- have the same staff care for you, whenever possible

- help you sleep well and not interrupt your sleep, whenever possible

- encourage you to get out of bed and walk around after surgery if possible

- remove any unnecessary tubes and drips as soon as possible

- encourage you to eat and drink and refer you to a dietician if this will help you.

You can help by making sure that you bring, to the hospital, your glasses, hearing aids, medication and anything else that might help your recovery.

What can help when I return home from hospital?

Anyone of any age and having any type of surgery is advised to have a responsible adult take them home and stay with them for 24 hours after leaving hospital. If you are well enough, you will be discharged the same day of the surgery. The risk of developing delirium is reduced if you return quickly to your familiar environment.

Once at home there are things that you can do to help your recovery and reduce the risk of developing delirium, for example:

- try to set a routine and some daily goals

- wear your glasses and hearing aids

- keep your brain active (for example, cross words or reading)

- follow the advice of your surgical team about taking medicine for your pain

- do any exercises that they have given you

- arrange to have support from family and friends and keep in touch with them regularly.

What can my family and friends do?

If you have been told that you might be at risk of delirium from the anaesthetic and surgery, you should let your family and friends know. You can show them this leaflet so that they can understand how to help you and what to expect after the operation.

More information on how to cope with delirium can be found in this booklet from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network which is for people who have experienced delirium, and for their carers.

When to seek help

If symptoms of delirium develop suddenly after you have started your recovery at home, it could be a sign of infection. You or people caring for you should seek advice immediately from your hospital or GP.

This leaflet has been produced by Leila Finikarides for the RCoA, in collaboration with patients, anaesthetists and patient representatives of the RCoA.

Disclaimer

We try very hard to keep the information in this leaflet accurate and up-to-date, but we cannot guarantee this. We don’t expect this general information to cover all the questions you might have or to deal with everything that might be important to you. You should discuss your choices and any worries you have with your medical team, using this leaflet as a guide. This leaflet on its own should not be treated as advice. It cannot be used for any commercial or business purpose. For full details, please click here.

Sixth Edition, November 2024

This leaflet will be reviewed within three years of the date of publication.

© 2024 Royal College of Anaesthetists

This leaflet may be copied for the purpose of producing patient information materials. Please quote this original source. If you wish to use part of this leaflet in another publication, suitable acknowledgement must be given and the logos, branding, images and icons removed. For more information, please contact us.