Your anaesthetic and the environment

The NHS is committed to reducing the carbon footprint of the health service and healthcare delivery. The Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Association of Anaesthetists are keen to reduce the carbon footprint of anaesthesia and provide guidance on environmentally sustainable practice in anaesthesia in the UK.

In this section you will find information on the environmental impact of anaesthesia. You may choose to use this information to ask your anaesthetist about your particular anaesthetic for your forthcoming procedure.

Environmental impact of anaesthesia – equipment, drugs and gases

The use of all anaesthetic equipment, drugs, gases, together with their packaging, comes with a carbon footprint. All of these require energy to develop, produce and transport.

Some items, such as face masks, are ‘single use’ to reduce the risk of passing on infections, so they need to be changed for each patient.

All anaesthetics and anaesthetic techniques require the use of electricity to power monitors and medical equipment. Some equipment is used in most procedures such as ECG sticky dots to connect your skin to the ECG heart monitor, blood pressure cuffs to measure your blood pressure, as well as cannulae placed in your veins.

Anaesthetic gases and drugs also have a direct effect on the environment. Some gases used in anaesthesia have an additional greenhouse gas effect. This means that once breathed out they continue to have a warming effect on the atmosphere for many years to come.

The ‘science’ bit

Carbon dioxide and carbon dioxide equivalence (CO2e)

The term carbon dioxide equivalency (CO2e) is used to describe the warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions in relation to that for carbon dioxide (CO2). As a rule, anaesthetic gases are 100s to 1000s times more warming than carbon dioxide. The CO2e for an anaesthetic can be calculated by multiplying the specific warming effect of the individual gas (the GWP100) by the actual mass of gas used for the anaesthetic and then breathed into the atmosphere.

The range of anaesthetic options

There is usually more than one way of giving your anaesthetic. The decision as to which is best for you for a given procedure will be discussed when you meet your anaesthetist before your procedure. This will largely depend on your clinical needs and the surgeon’s requirements for your particular surgery. Your safety during surgery is paramount therefore clinical concerns may have to override any environmental concerns.

Anaesthetic options that are better for the environment

For some procedures local anaesthetic alone can numb a part of your body for surgery or a procedure. For example, hip replacement can be undertaken with a spinal injection in which very little drug is used yet is very effective. Some operations on the arm can be performed using a nerve block, to numb the nerves in the arm. Not all procedures, though, can be undertaken with local anaesthetic alone.

Anaesthetic options with low warming effects

There are anaesthetic gases in common use that have less impact on the environment. One is called sevoflurane. An hour's anaesthetic will have the warming effect of 800–1,600g CO2, the equivalent of driving 5–10km.

Alternatively a mix of intravenous drugs can be given by injection – this is referred to as Total Intravenous Anaesthesia or TIVA. No anaesthetic gas is used with this technique, but there is still an environmental impact of its use.

Anaesthetic options with moderate warming effects

These anaesthetics are 100s of times more warming than local anaesthetic alone.

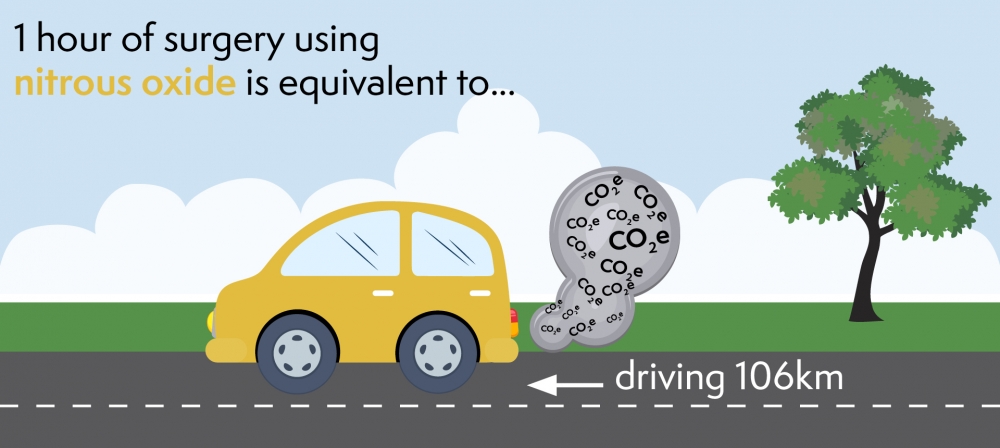

For example, if nitrous oxide (laughing gas – N2O) is used as part of your anaesthetic, it significantly increases the environmental effect of your anaesthetic. This means that using 500ml of nitrous oxide every minute for a procedure lasting an hour will warm the atmosphere by an equivalent of 16kg CO2. That is the same as driving a small car 106km. Nitrous oxide is often used in large volumes and remains in the atmosphere for 110 years, during which it continues to have a warming effect.

Reducing use of nitrous oxide would lead to one of the most significant reductions in anaesthesia related CO2e.

Anaesthetic options with very high warming effects

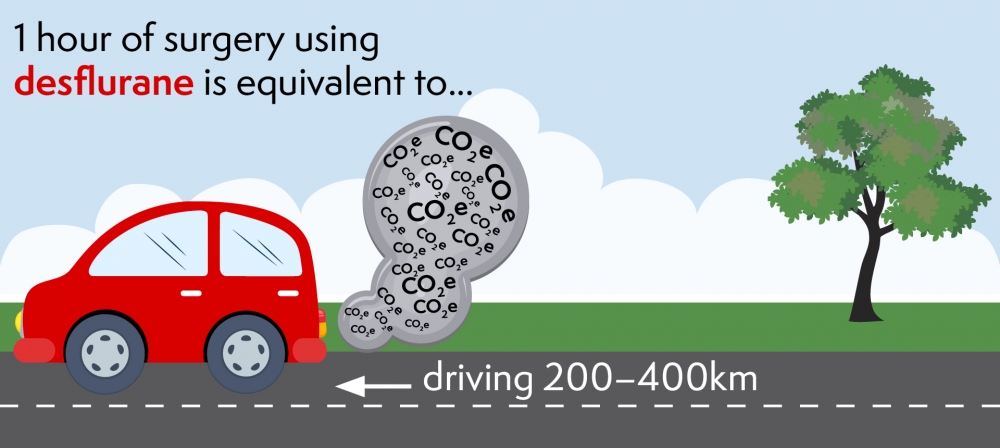

There is one gas called desflurane that is over 2,500 times more warming than carbon dioxide. That means that an hour's anaesthetic with this gas will warm the atmosphere by the equivalent of at least 30–60kg CO2, the equivalent of driving 200–400km.

Why do anaesthetists use gases that are so warming?

There are characteristics of some of these gases that are beneficial for certain patients, for example those who have obesity. The choice of anaesthetic is based on your particular clinical needs as well as the surgical requirements. The type of anaesthetic gas or technique used does not affect the experience of anaesthesia. You will be asleep and pain free with any of the above general anaesthesia options.

What do anaesthetists do to reduce the impact of anaesthesia on the environment?

Over recent years, individual anaesthetists have been successful in reducing the use of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide. With the help of manufacturers, they are also reducing the wastage of those anaesthetic gases. Modern anaesthetic machines and advances in equipment allow anaesthetists to safely use smaller amounts of anaesthetic gas. This reduces the wastage and therefore minimises the impact of these gases on the environment. There are also ventilation systems to remove these waste gases from the operating theatre environment.

Anaesthetists are very conscious of the need to reduce unnecessary plastic and to encourage hospitals to do more to recycle packaging and equipment. Hospitals and manufacturers still have a way to go, but packaging and recycling is now becoming an important factor in reducing the carbon footprint of the NHS.